Follow us on:

|

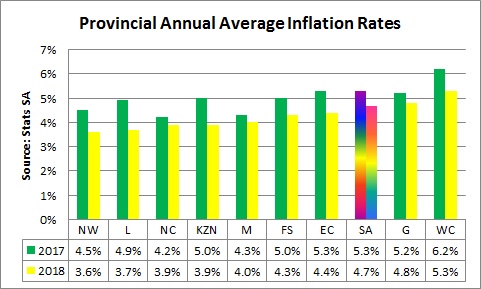

Provincial rates show large dispersion between 5.3 per cent and 3.6 per cent

Inflation rates were highest in areas of South Africa most affected by years of drought [PREUSS]

The consensus expectation by economists in the first quarter 2018 was that inflation would average 4.9 per cent in 2018 after a 5.3 per cent average in 2017.

This was largely due to an expected slowdown in food inflation. The South African Reserve Bank (SARB) in its March 2018 Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) statement had the same forecast.

The provincial rates show a large dispersion between 5.3 per cent and 3.6 per cent in 2018, even though it is not as large as the range between 4.2 per cent and 6.2 per cent in 2017.

The reason for the wide dispersion is mainly due to meat and fuel prices, as the poorer rural provinces have a far lower weight of these two factors in their consumer price basket than those of the richer provinces of Gauteng and the Western Cape.

The 2016 drought resulted in high food prices for the majority of the population, but in 2017 there was a divergence as meat prices soared as herds were rebuilt after the drought. These meat prices started moderating in 2018, which is why there is less dispersion in that year compared with 2017.

The other factor is fuel prices, as the rural population mostly walk to work, whereas in urban centres, workers have to use private or public transport as their work places are generally not within walking distance.

Inflation rates in South Africa

The drought also did not hit all places equally as the summer rainfall areas largely recovered in 2017, but drought continued into 2018 for the Eastern Cape and Western Cape.

The drought-hit Western Cape had the highest provincial rate with a rate of 5.3 per cent for 2018, while Gauteng had the second highest inflation rate at 4.8 per cent. All other provinces had rates below the national average of 4.7 per cent with the North West the lowest at 3.6 per cent.

The pressure on disposable incomes for most of 2018 meant that meat inflation progressively eased during the year so that the December meat inflation slipped to 1.8 per cent year-on-year (y/y) in December 2018 from a recent peak of 15.6 per cent y/y in September 2017.

The recent outbreak of foot and mouth disease in Limpopo has meant that South Africa for the moment is unable to export beef and other cloven-hooved meat, so meat prices are likely to ease further in 2019.

Wandile Sihlobo from the Agricultural Business Council expects high food prices this year, but the increases will not be as high as those of 2015 and 2016.

“The lower agricultural commodity prices that underpinned 2018’s downward trend are showing a drastic reversal as persistent dryness in the western parts of SA’s maize belt lead to lower-than-expected maize plantings and a general expectation of a poor harvest in the 2018/19 season. Earlier this week SA’s white and yellow maize spot prices were up by 66 per cent and 44 per cent, respectively, from the corresponding period in 2018, trading around R2,807/ton and R3,127/ton,” he said.

“In 2019 SA’s food prices are likely to increase at a relatively slower pace than 2016 and 2017, with a possible average of about 5 per cent despite the uptick in maize prices. The reason for this is that while maize prices have increased, the current levels are nowhere close to the R4,000/ton level we saw in 2015 and 2016, partly because of the high carry-over stocks, which has somewhat cushioned the country’s maize supplies,” he concluded.

In contrast to meat prices, fuel prices moved higher during 2018 and the Gauteng petrol had a peak y/y increase of 24.6 per cent in July before ending the year with a 3.3 per cent y/y rise.

The y/y decline of 2.8 per cent seen in January 2019 is likely to continue for most of the rest of the year as base effects will result in large y/y declines compared with the high prices that took place in the middle months of 2018.

That is why the SARB expects inflation to average only 4.8 per cent in 2019 whereas the consensus forecast of economists surveyed by the Bureau for Economic Research is for a mild rise to an average of 5.2 per cent.

Given that meat and fuel prices are expected to have moderate increases this year, the dispersion of provincial rates is also likely to be less as well.

By Helmo Preuss in Johannesburg, South Africa