Follow us on:

|

With only weeks to go to Brexit’s target date, there is deadlock in the British parliament, recriminations on both sides, and, writes Russell Merryman, a growing realisation that what was promised might be impossible to deliver.

Anti-Brexit sentiment is growing as the deadline for Article 50 approaches [MERRYMAN]

With the box closed, nobody knows if the cat is alive or dead, and so it simultaneously exists in two states at once.

As it is with quantum mechanics, so it is with Brexit. With only a few weeks to go before the self-imposed target of 11:00pm GMT on March 29th, 2019, British politicians are fighting it out in parliament and in the media trying to figure out a way to ensure that the country does not accidentally walk off the edge of an economic cliff at that date and time, ending up with No Deal.

If that happens, all bets are off.

The UK is in uncharted territory, Terra Incognita.

All EU laws, agreements and licences, including free-trade agreements with more than 60 other countries outside the EU, would cease to apply, literally, overnight, leaving the UK in a situation where planes might not be able to fly, because they currently do so under EU Safety licences; lorries queueing for miles at British and European ports for tariff and border checks, and thousands of businesses which currently rely on just-in-time supply chains grinding to a halt, including the automotive and aerospace industries.

The UK Government is stockpiling food and medicines to mitigate such effects on the public, and they have warned businesses to do the same, although without providing specific information, an approach which has angered business leaders and company owners across the country.

Some multi-nationals have already voted with their feet, moving their European headquarters onto mainland Europe to maintain their presence in the world’s largest trading bloc, while others say they may do the same with their factories, threatening thousands of jobs in the UK.

Deadlines and Deadlocks

Meanwhile as the clock ticks, the politicians are deadlocked. The Withdrawal Agreement that was negotiated by Theresa May’s team was thrown out by MPs who inflicted one of the biggest ever defeats on a sitting government. With the only plan on the table now in tatters, the Government is desperately trying to find a way forward, knowing that the European Union will not renegotiate the current agreement, and that there is no appetite in parliament for the economic disaster of No Deal.

The problem with the current deal is that for those MPs who support Brexit, the Withdrawal Agreement did not go far enough; it would leave the UK having follow the EU rules on customs and the single market during the transition period, without having any say in how those rules were shaped.

This was BRINO, said the Leavers: “Brexit in name only”, which left Britain as a “rule taker” or a “vassal state”. Meanwhile for MPs who support staying in the EU, the agreement went too far, so Mrs May faced an unholy alliance of leavers and remainers who inflicted a 230-vote defeat on her precious deal.

The other major problem with deal is the issue of the Irish border. When they agreed to implement the so-called “will of the people”, the Government promised there would be no hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland – potentially the only land border between the UK and the EU after Brexit.

This promise immediately made the Government negotiators hostage to fortune, as there is currently no way of carrying out the necessary checks on goods and people at that border without having a physical presence, as required by all international trade, including the WTO. Kites have been flown about “technological solutions” for a “frictionless border” but there is still no sign of these.

The open border is also enshrined in the Good Friday Agreement, an internationally recognised treaty which brought peace to the island of Ireland in 1997, and which is sacrosanct to politicians on both sides of the frontier, all of whom have criticised some of the Brexit ultras who seem content to throw the hard-earned peace under the bus to achieve their dreams.

“Once and for all?”

Opinion polls show growing support for Remain (58-42% in some cases) and campaigns like #RemainerNow where Leave voters admit they were wrong and say they would now vote to stay [MERRYMAN]

The Act that was passed almost completely guaranteed chaos whatever the outcome. The vote was only advisory, which meant there was no threshold set which would have made it constitutionally binding, such as a 75 per cent turnout; while millions of voters, including EU nationals living in the UK and UK ex-pats living abroad, were not given a vote.

This also meant the referendum was not subject to the Venice convention which would have made it void if there was evidence of campaign overspending, which, it transpired, there was.

The campaign itself was divisive and in future there will be whole books and Ph.D theses written on the way the Leavers built a campaign on emotion-tugging exaggerations, outright lies and propaganda while simultaneously dismissing the facts and evidence of the Remain side as “Project Fear”.

The result was a wafer thin 51.9 per cent Leave to 48.1 per cent Remain on a 72 per cent turnout. Two countries in the union, Scotland and Northern Ireland, along with Gibraltar, voted to stay, England and Wales did not.

A sensible government would have reacted with caution to this split decision, but the recklessness of the Tories continued. After Cameron ran away from the result, the new leadership doubled down, claiming “Brexit means Brexit”, mis-represented the advisory vote as a mandate and promised to deliver the so-called “will of the people” despite plenty of constitutional experts and mathematicians pointing out that while 52% was a majority, on a 72% turnout, only 37% of the electorate actually supported Brexit.

Although she had campaigned to Remain, Theresa May, like most MPs, had been spooked by the result; many Remain-supporting MPs suddenly found themselves representing constituencies which voted to leave, and the mob scented blood. The Leave campaigners pushed home the advantage, even though they had no majority in Parliament and no single party with a mandate to deliver on their promises; they knew they had to get a largely Remain-supporting Parliament to start delivering the referendum result, before reality set in and people realised that what they were promised was impossible.

They wanted Article 50 of the Treaty of the European Union, the agreed two-year process by which a member could leave the bloc, to be triggered immediately. Legal action was taken to ensure that the decision to trigger Article 50 was taken by Parliament, not the government alone; in the end it was.

Then, having set the clock ticking Theresa May dithered some more, called a General Election to try and strengthen her mandate, which failed and left her without the majority that the Tories had won in 2015.

Impossible incompetence or incompetent impossibility

The whole negotiation process was incompetent; the UK set out red lines which most sensible people knew were impossible to deliver on, including the “frictionless movement” across the Irish border, then tried to argue about the rules, which the EU stuck to rigidly and consistently, as any neutral observer knew they absolutely would do.

The Withdrawal Agreement, when it came, included a transition period where the UK would remain aligned to the EU, and an insurance policy, or backstop, which ensured that there would not be a hard border in Ireland if the other solutions that had been promised did not deliver.

The terms of the transition were the tipping point for the Brexit ultras, who condemned the deal and said they would vote against it.

More political games ensued, the ultras tried to oust Theresa May in a Tory leadership vote in December 2018, which they lost, then the government delayed the vote on the deal until January 2019 in a bid to try and convince the ultras to support it. They didn’t.

Now we have a deal that has little support in Parliament, but is the only agreement in town according to the EU; a government that cannot command a majority for the deal, but can just scrape enough support to survive a vote of no confidence, and an Opposition party which is on the fence over Brexit, still scared of their Leave-voting constituencies, but who know that Brexit is a time bomb that they don’t want to be left holding when the music stops.

So they call for a General Election, which they know they can’t get because their motion of no confidence in the government failed.

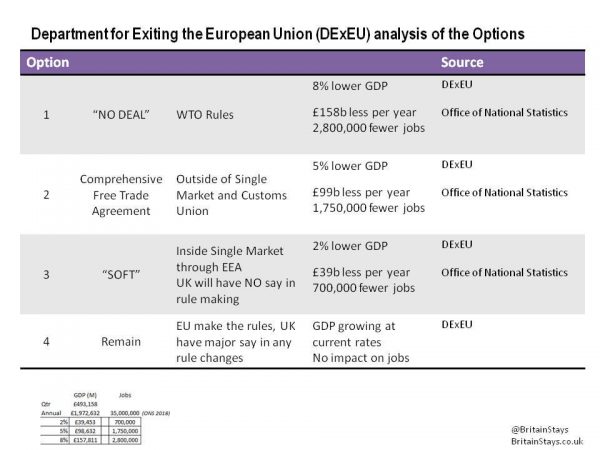

Now the talk is of cross-party agreements to try and get around the parliamentary impasse, which the right-wing press and the Brexit ultras ironically complain is a “plot is steal Brexit from the people”. The government has to get Parliamentary approval for a deal, while MPs are trying to ensure the country does not crash out of the EU without one. Almost all reputable economists agree that would be a disaster for the country, which could cut the UK economy by 8%, putting 2.8 million people out of work. This represents an unprecedented blow compared to the 2.5% drop suffered in the 2008 financial crash.

None of the Brexit options are painless for the UK economy [UK Government]

The EU Referendum Bill alone took six months and still managed to be a complete mess. One of the outstanding bills, the Trade Bill, was considered close to completion, but was recently shelved by the House of Lords because it lacked detail. And all of that before the politicians have realised that they still have to tackle the impossibility of the Irish border.

A second referendum

So, now the imperative is to avoid No Deal. There are options, and it has to be remembered that this whole sorry state of affairs has been entirely self-inflicted, but this also means that it is in the gift of the UK Parliament to end the misery at any time before March 29th by revoking Article 50. While it may be a hard sell to the Brexit ultras, the right-wing press and the people who voted for Leave, it would prevent more serious and immediate damage to the country’s economy and does not preclude the UK trying again in the future.

There is growing pressure for a second referendum, to put it back to the people.

Those supporting Remain are in favour of a fresh chance to put their case, and they claim that an electorate ratifying their own decision, now that they know more about the issues and their complexities, is the only democratic thing to do. Brexiters meanwhile cry foul, saying it would be a “betrayal” and that the original result must be honoured, despite its problems.

They also know that for the floating voters, their false promises and outright propaganda probably won’t work a second time, while the opinion polls show growing support for Remain (58-42% in some cases) and campaigns like #RemainerNow where Leave voters admit they were wrong and say they would now vote to stay. The country, like parliament seems deadlocked.

Outside observers have been more forthright, especially in Ireland, the EU country which has the closest relationship with the UK and therefore has the most to lose if there is no deal. Fintan O’Toole of the Irish Times and Tony Connelly of the state broadcaster RTÉ have long pointed out the paradoxes at the heart of what the Leave campaign promised, and the fact that they did so and then thrust the implementation of a poorly-run referendum on an unwilling Parliament.

O’Toole has been especially scathing, writing in The Guardian that the possibility of Brexit disappeared almost as soon as it touched reality, when the result was announced, and that the Leave campaign was an impossible dream, compounded by an incompetent government and negotiators who thought they could work around the implacable and united EU team, who knew their position had been clearly laid out by all 27 members, including Ireland.

As a result, Ireland was able to punch way above its own weight, knowing the EU had its back. They wanted to avoid a hard border, to protect the Good Friday Agreement, and to preserve the rights of everyone on the island of Ireland, including Northern Ireland, to continuing Irish citizenship. Supported by the rest of the EU they got exactly that in the Withdrawal Agreement, much to the dismay of the Brexit ultras, who, rather than reflecting on their own lack of clear objectives and skills, added the Irish Government to their list of people to blame.

And this underpins the whole failure of Brexit. When the clock was started nobody really knew what Brexit meant beyond the overhyped, delusional rhetoric of the Leave campaign. “Brexit means Brexit” came the monotone reply from May and her cabinet. Experts, MPs, journalists and the right-wing press have spent much of the last two years arguing about it, with all kinds of options put on the table, including European Free Trade Association membership, Norway-Plus, Norway-Plus-Plus, Canada-Plus, Canada-Plus-Plus-Plus, Single Market and Customs Union Associate membership and World Trade Organisation-only – almost fifty shades of Brexit.

Meanwhile the public is sick of it, and most just want it to end. More than 700 thousand people marched through London in October 2018 calling for an end to Brexit, hundreds more protested outside Parliament on the evening of the Withdrawal Bill vote; social media is awash with competing memes and articles, while fake news about made-up versions of existing treaties and opinion continue to swirl around, adding to the febrile environment. The potential failure of Brexit has also led to an upsurge in populism, with the French “gilet jeaunes” campaign being hi-jacked by Brexit ultra campaigners (most of them aligned with the far right) who have harassed and abused politicians and journalists who disagree with them.

Meanwhile the media is entrenched with newspapers fighting their original corners, and broadcasters like the BBC, who have been bullied by successive governments for years, supinely trying to present both sides, even though the learning process of the last two years has left us knowing that there is only false balance, which means that every expert voice from business or parliament stating facts and evidence is countered with the fact-free, original mantras of the Leave campaign from a Brexit ultra.

The Leave supporters always knew this would be case; they never needed facts and evidence, they only needed feelings, emotions, which made for a good campaign, but it never stood up to scrutiny in the cold light of day.

The Leave campaign may have commanded an absence of facts, the reality however, is that policies, plans, negotiations and treaties about real things like trade, logistics and people absolutely rely on them; you cannot build a stable economic future on a foundation of feelings and false promises.

Now, with the deadline approaching, no sign of a way forward in Parliament, and the blame game in full swing, the next few weeks will prove crucial and will determine the state of the British economy and the country’s position and relevance on the world stage for generations to come.

The question now though, is whether the Government (or indeed, the Opposition) is brave enough to open the box and find out whether Schrödinger’s Brexit is alive, or dead. The UK cannot go on with them believing it is both for much longer.

Russell Merryman is Senior Lecturer in Journalism at the London College of Communication, former editor-in-chief of web and new media at Al Jazeera English, prior to which he was a broadcast and multimedia journalist, presenter and editor at the BBC.